State DOTs and other government agencies in the US are showing a steadily increasing interest in "progressive" delivery models, and several recent megaprojects have adopted this model for their delivery, including in transit (the Sepulveda Pass Transit Corridor and the San Jose Airport Connector), highways (the I-495/I-95 Capital Beltway), and social infrastructure (the Potrero Bus Yard Modernization).

There are numerous progressive delivery models, such as construction manager at risk ("CMAR"), construction manager/general contractor ("CM/GC"), pre-development agreements, progressive design-build and progressive P3. Fundamentally, progressive contracting seeks to drive a benefit from (i) engaging contractors1 earlier than is typical under fixed-price contracting (i.e., during project development) in order to allow for collaboration between the owner and contractor to properly identify, understand, manage and mitigate project risks and challenges before pricing is agreed; and (ii) fix the price for the performance of construction work later than is typical under fixed-price contracting (i.e., after contract award), once the risks and challenges are identified, better understood and can be managed and mitigated – and therefore more reliably priced. These features are foundational to the progressive contracting model and seek to reduce uncertainty with respect to project risk, which in turn should lead to more reliable pricing and less claims and cost and schedule overruns.

The use of progressive contracting is not new and has been used in other markets for years, but until recently was less frequently considered for use on US public transportation projects.

This article explains:

- the key elements of the "typical" progressive contracting model;

- key reasons why a project owner might consider utilizing a progressive contracting model for project delivery; and

- "guiding principles" for project owners to consider so as to implement progressive contracting successfully.

KEY ELEMENTS OF A "TYPICAL" PROGRESSIVE CONTRACTING MODEL

How does progressive contracting typically work?

Progressive contracting is an umbrella term we use to describe contracting models that engage a contractor to work collaboratively with the project owner before a price for construction is fixed so that pricing is done with better knowledge and understanding of the project. For the purpose of providing a simple frame of reference, we describe below what we consider to be a fairly "typical" structure for a progressive contract. However, the terms of progressive contracts vary considerably, and some projects take a significantly different approach from that described here.

Under a "typical" progressive contracting model, a contractor is selected through a competitive solicitation that is evaluated on a qualifications-only basis or qualifications plus an aspect of price (e.g., preconstruction phase costs, management fee, equity return/profit or margin percentage). Therefore, procurement and selection of a contractor is typically completed relatively quickly.

Following contractor selection, the contractor enters into an arrangement to work collaboratively with the project owner during two phases:

- Phase 1 - the preconstruction phase. This phase is for the development of the project, including the resolution of key scope and risk issues. Activities during this phase can include: project planning, scope definition, feasibility analysis, public/stakeholder engagement, assistance with environmental permitting and other approvals, design development, risk mitigation, preparation of contract documents and specifications for construction, and potentially early construction works. Some projects also split this phase into a separate planning phase that proceeds preconstruction activities, allowing for better sequestration of activities to be performed concurrently with the environmental review and approval process.

- Phase 2 - the implementation phase. This phase is for the implementation of the project and depending on the delivery model utilized may include final design and construction of the project and beyond (e.g., operations and maintenance services).

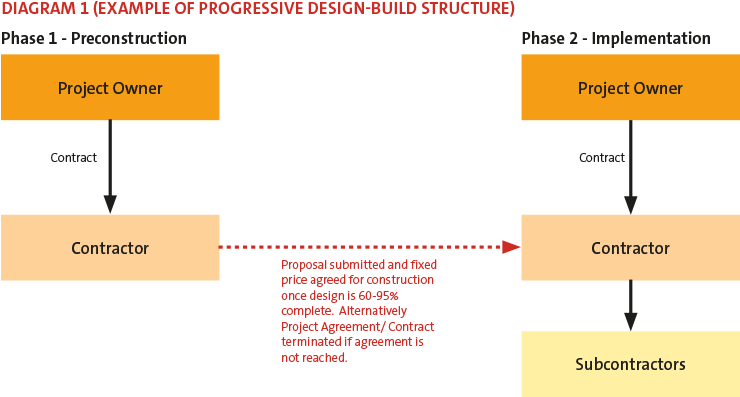

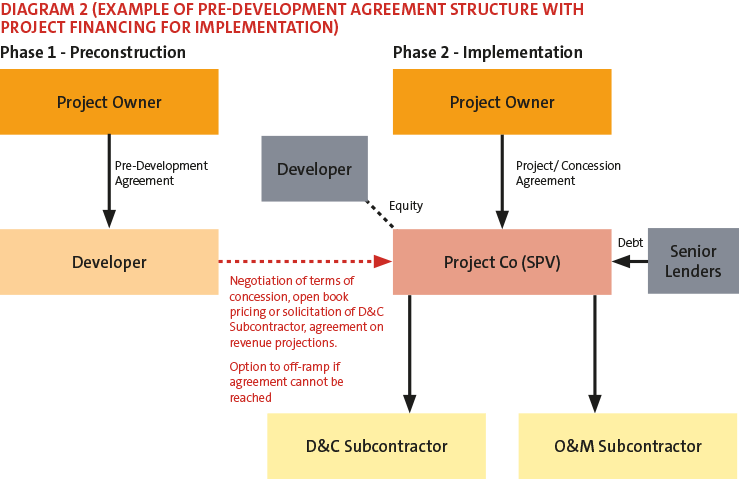

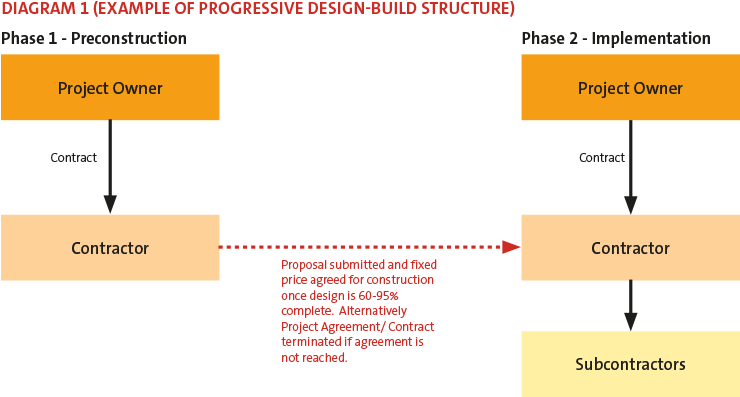

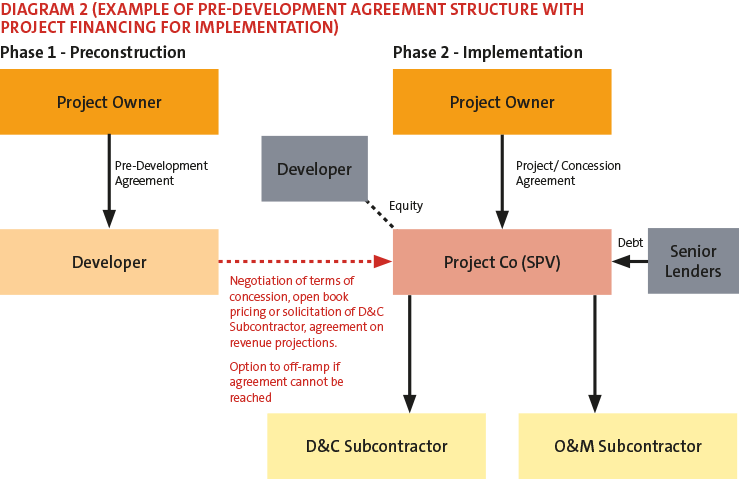

See Diagram 1 (illustrating a progressive design-build structure) and Diagram 2 (illustrating a pre-development agreement structure with project financing for implementation).

The preconstruction phase typically includes an iterative build-up of the project scope, schedule and cost estimates on a transparent "open book" basis or through the competitive bidding of subcontractors, with the final contract price for the implementation phase established at a later stage of design development (for example, at 60–95% level of design) than is typical for a fixed-price design-build contract (about 15-35% level of design). An important differentiator of progressive contracting is that the price for the implementation phase is established at the point at which the project scope and schedule can be clearly defined, and risks are well understood and efficiently allocated so that parties can plan and price the project in a more informed manner. Once this point is reached, the contractor typically submits a proposal to the project owner for the implementation phase with a defined scope, schedule and price for the project owner's acceptance.

If the project owner accepts the contractor's proposal, the contractor completes the project in accordance with the agreed scope, schedule and price. However, if the parties cannot reach agreement on the contractor's proposal, the contract documents typically contemplate one or more "off-ramps" during the preconstruction phase that may be exercised by the project owner to terminate the relationship with the contractor.

If the project owner exercises an "off-ramp": (i) the contractor will not proceed to the implementation phase; (ii) the preconstruction phase will expire; and (iii) the project owner will typically have the right to use the designs and other work product prepared by the contractor during the preconstruction phase in any subsequent re-procurement for project implementation (i.e., the project owner may pursue re-procurement of the implementation phase separately).

Payment terms during the preconstruction phase vary significantly and it is difficult to define what is "typical", but usually the project owner will make payments to the contractor during the preconstruction phase on either a service agreement or a milestone payment basis; and it is not uncommon for some preconstruction costs to be carried by the contractor at risk until a fixed price is agreed and the implementation phase begins.

In summary, a "typical" progressive contracting model allows for:

- Earlier identification by the parties of scope, schedule and cost challenges, and an opportunity to identify, understand, manage and mitigate "unknown" risks. This occurs before the parties commit to a price for the implementation phase. The information that is gathered by the parties during the preconstruction phase can reduce guesswork and improve decision-making, allow for efficient allocation and management of project risks and thereby improve certainty and predictability with respect to project implementation. For example, with respect to the risk of design approvals by third parties having jurisdiction over the project, this model allows for the contractor to engage with such third parties during development of the design to address their concerns before fixing the price and the schedule for construction.

- Later identification of the price for the implementation phase. This occurs after front-end due diligence by the contractor during the preconstruction phase and at a point in time when "unknowns" may be identified and understood, and can be more reliably priced, as informed by the contractor's work during the preconstruction phase. This can help reduce the contractor's risk premium and contingencies in the pricing of the implementation phase, resulting in better value for money for them project owner. It can also help reduce the risk of unforeseen costs by way of change orders and claims during project implementation. In short, progressive contracting allows for informed discussions between the parties on cost drivers and value trade-offs.

KEY REASONS TO USE (OR NOT USE) A PROGRESSIVE CONTRACTING MODEL

When to use progressive contracting?

A project owner might consider utilizing a progressive contracting model where one or more of the following conditions exist:

- Where contractors have shown a loss of appetite to accept or aggressively price difficult risks on a fixed-price basis and are more selective in the projects they pursue and contracting models they agree to – a trend that could continue in the current environment of high inflation, unpredictability in supply chains and a tight labor market. In this scenario, a project owner may get better participation from the contractor market if the project owner adopts a progressive contracting model. The 'sunk cost' procurement risk for contractors may also be lower under a progressive contracting model given that such procurements are typically shorter in duration and cheaper to bid than a fixed price "hard bid" procurement. This may also encourage better participation from the contractor market.

- Where the scope of work for the project cannot be priced accurately upfront (i) because the proposed scope is variable or uncertain; or (ii) due to complex design, schedule, sequencing, buildability or technology issues, or other issues that may not be well understood at the time of bid. Here, contractors may perceive that they are being asked to take on an unquantifiable risk if they are asked to price the project implementation work upfront, or the project owner will be required to take on a risk that it cannot control. In this scenario, as explained above, progressive contracting may allow for risks to be considered and managed in a collaborative manner and be well understood by the parties prior to pricing being fixed. For example, overstation development projects that include the development of housing (including affordable housing) and/or commercial or retail on top of a transit station or other facility may include complex schedule, sequencing and buildability issues, including with respect to the timing and availability of public funding sources, which could benefit from collaboration between the public owner and contractor at an early stage and throughout project development. Also, progressive contracting aligns well with projects that involve systems engineering for emerging technology, where iterative design and testing is required to get to project implementation.

- Where the time for delivery is paramount. Progressive contracting can accelerate project development by allowing for planning, procurement, environmental/permitting and development activities to occur in parallel. Fixed-price bids require the project to be "ready" to bid, with the owner having already largely defined the project scope, schedule and risks; whereas this level of definition may not be needed for the procurement of a contractor under a progressive contracting model, given that the preconstruction phase work to be performed by the contractor will inform the definition of scope, schedule and risk.

- Progressive contracting can also accelerate the construction of a project by including the collaborative identification of discrete early works packages as part of the preconstruction scope of work (often as part of the risk management process or with a view to optimizing the implementation phase construction schedule), and performance of those early works during the preconstruction phase. Early works may also include the procurement of long lead-time items during the preconstruction phase.

- In addition, innovations and construction efficiencies to accelerate delivery of the implementation phase can be identified early and contractualized during the preconstruction phase.

- Where it is important for project owners/stakeholders to retain input and control over project outcomes before price and schedule have been fixed. The collaborative nature of progressive contracting, including the iterative build - up of project scope, schedule and cost estimates, allows significant opportunities for project owner input and control throughout, including, for example, preliminary screening of different alternatives and during the preparation of a proposal for the implementation phase. This feature is an important differentiator from some other forms of fixed-price contracting, where bids are developed based on a static set of specifications without the project owner's ongoing input and feedback, and are made and accepted on a "take it or leave it" basis.

- Where private sector expertise, know how and innovation is required for early project decisions (e.g., with respect to the optimal technology solution, the approach to project risks, or the scope/feasibility/affordability of the project). The information shared by the contractor during the preconstruction phase can be used by the project owner to help it make more informed decisions with respect to project development on a value for money basis. For example, the project owner has visibility of anticipated project costs throughout design development and may choose to descope some elements to stay within its affordability threshold/ project budget.

When not to use progressive contracting?

A progressive contracting model may not be the right model for:

- straightforward, routine or repetitive projects, where scope and risk are well understood;

- projects that do not require unusual or extensive planning; and

- projects that do not require detailed design to be priced accurately, or where the design is able to be fully developed with a clear and straightforward scope.

Also, if a project involves a concession or revenue to the private sector, then revenue projections may be very difficult to "negotiate" on a "open book" basis. A project owner may be able to drive better value from a revenue stream in a competitive bidding environment.

FIVE GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR SUCCESSFUL IMPLEMENTATION OF A PROGRESSIVE CONTRACTING MODEL

If the project is a good fit for progressive contracting, project owners should consider these five guiding principles when crafting and implementing a progressive contracting model for project delivery:

- Ensure reasonable certainty of a deliverable project Progressive contracting should not be used as a "fishing expedition" to try and engage the private sector to kick-start a difficult project with many unknowns. This is because, given the significant resource commitment required to bid on a project and engage in preconstruction activities, prospective contractors may condition their pursuit of a project on the project owner being able to demonstrate that the preconditions exist for a deliverable project that has a high likelihood of successful implementation. Further, engaging a contractor too early in the project development process before they can really add value may be confusing and not benefit anyone.

As a general rule, prospective contractors may look for the following preconditions to exist before bidding on a project:

- A level of political support for the project and an active project champion who will remain in office through project implementation.

- Identification of a reasonably certain funding source for the project or a credible forecast of project revenues (although for some projects the contractor may be willing to help the owner identify viable funding sources as part of the scope of work for the preconstruction phase).

- Project owner buy-in for a "progressive" approach to project delivery. Often a significant hurdle here is ensuring that stakeholders who are used to fixed-price contracting are accepting of a model that fixes the price of project implementation outside of the RFP stage.

- The project owner's capacity and capability to deliver the project. Progressive contracting requires a depth of project owner resource – both staff time and financial resources - because the project owner needs to work collaboratively with the contractor throughout the preconstruction phase.

- A governance structure that accommodates progressive contracting, ideally allowing for: delegation of authority, clear lines of communication and decision-making authority, streamlined information transfer and cross-pollination of ideas, prompt issue resolution, and alignment of objectives.

- Legal authority to deliver the project under a progressive contract.

2. Maximize opportunities for optimization of project risk management on a value for money basis

- Risk allocation has significant implications for contractors (and other project stakeholders including, if applicable, equity and debt financiers).

The preconstruction phase provides an opportunity for project risks to be identified, further defined, understood, mitigated and/or managed, and not simply "allocated". Mitigating and/or managing these risks during the preconstruction phase allows for the parties to better understand and predict the project scope, schedule and price for the implementation phase. This allows for better decision-making. Some mechanisms to understand, mitigate and/or manage risk are listed below. These mechanisms should be considered by project owners for inclusion in the contractor's scope of work for the preconstruction phase:

- Preconstruction site investigations and surveys

- Assistance with the project owner's coordination of right-of-way acquisition, including identification of any additional land required for the project

- Active engagement with third parties, permitting agencies and utilities with necessary design development to facilitate this

- Involvement in the community or stakeholder engagement processes surrounding the project

- Development of the design to a prescribed level

- Contractor proposals for risk mitigation during the pre-construction phase

- Review and preparation of a written evaluation of project risk allocation or risk register with a recommendation for various approaches to such allocation and compensation mechanisms for unavoidable risks so as to achieve value for money and minimize risk contingencies in pricing the implementation phase work. A risk register can also allow for better identification, mitigation and management of important key risks that are project-specific (as opposed to generic).

- Value engineering proposals to optimize project scope and budget

- Integration of design development with construction planning at an early stage, including a review of requirements for the implementation phase to clarify uncertain, unnecessary or inadequate scope or construction requirements. This could include recommendations for the construction schedule and phasing, staging and temporary work, traffic management, minimizing construction impacts, and interfacing contractors and projects. This can help to optimize construction efficiencies and drive value.

3. Consider reimbursing preconstruction scope costs

- Project owners may believe that contractors will be willing to finance the cost of performing preconstruction phase work, thereby simplifying the project owner's

approval process and deferring its obligation to fund the project. However, this is rarely true.

- It is most common for contractors to be reimbursed by the project owner for all or some of their costs for preconstruction services on a periodic or milestone basis

during preconstruction.

- However, some projects may be able to take a different approach to preconstruction cost reimbursement, by deferring all or part of the reimbursement to the implementation phase. Contractors are most likely to be willing to take some level of risk around preconstruction costs on (i) projects involving new technology where the contractor has a development budget towards implementing the project; and/or (ii) concession or revenue risk projects with an opportunity for significant financial reward or upside during the implementation phase. Project owners should note that contractors will generally be very incentivized to reach the implementation phase, even without having an element of their costs at risk. This is because they will view the project as a failure if they do not get to the implementation phase given that the fees that they generate from project development are usually not their core business, and their opportunity for revenue and profit may be highest for the implementation phase.

- For some projects, it may be that the cost of performing the preconstruction phase work can be included as a bid item during the solicitation so as to maximize competitive tension among the bidder pool and drive value for money for the owner with respect to the pricing of such work. For example Maryland DOT is delivering its I-495/I-270 P3 program through a progressive P3, and it required proposers to bid a price cap for their preconstruction services, which was evaluated as part of the selection process.

4. Apply mechanisms to mitigate a perceived lack of competitive tension in establishing the price for project implementation

Project owners may be concerned that the technical solution, commercial terms, risk allocation, and price for project implementation are negotiated with the contractor during the preconstruction phase with a perceived lack of competitive tension from other bidders. However, there are mechanisms that project owners can implement to address this concern:

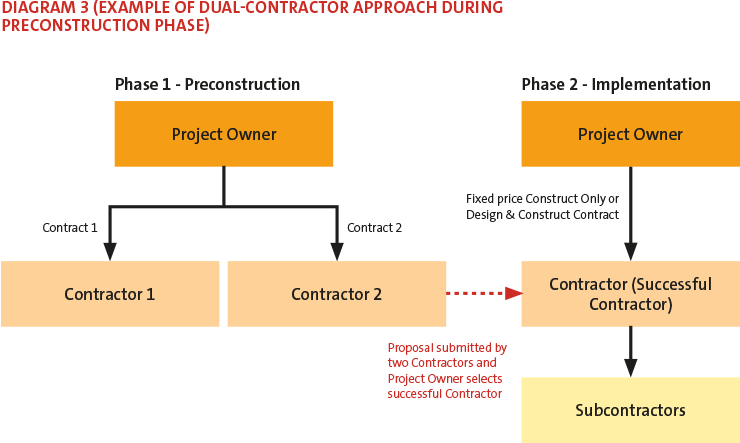

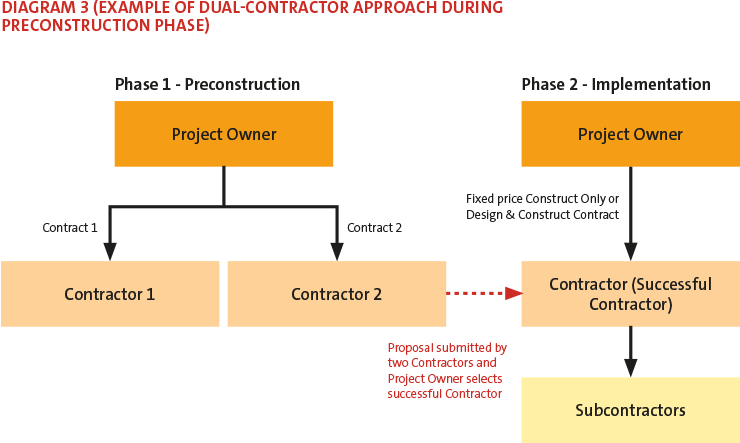

- Appoint two contractors to separately perform the preconstruction phase work – the proposal for the implementation phase can then reflect technical and price competition between these two contractors. See Diagram 3, which illustrates this model. For example, the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority ("LA Metro") adopted this mechanism for the Sepulveda Transit Corridor Project, contracting with two separate contractors to perform preconstruction phase work, each with a different transit mode (LA Metro did not specify a required transit mode, alignment or configuration in the original solicitation). When LA Metro selects a locally preferred alternative for the project, it can elect to continue to proceed with one contractor if its proposal for project implementation is consistent with the locally preferred alternative, and the contract with the second contractor will expire.

- "Price anchors" that are competitively bid by contractors during the RFP stage. These "price anchors" may include, for example: a competitively bid fee, equity return/profit or margin percentage for the work to be performed during the implementation phase. "Price anchors" are committed prices and are not renegotiated in the build-up of the construction price for the implementation

phase.

- Include in the scope of work for the preconstruction phase an iterative build-up of the design, schedule and price with multiple milestones or "validation points" in order to compare those prices against an independent cost estimate or benchmarks with an ability for the project owner to exercise its right to "off-ramp" if value for money is not being achieved. Both the "validation points" and the "off-ramps" will need to be clearly defined and objective. We note that the viability of "off-ramps" will depend on the project owner's view on the cost and schedule impacts of the delay caused by a re-procurement after exercising the off-ramp. The viability of off-ramps will be improved where two contractors are appointed to perform the preconstruction phase work (as referred to above) or where the owner is in a position to quickly re-procure the implementation phase scope.

- Transparent "open book" cost estimating to develop pricing for the implementation phase. If the project owner does not have experience in "open book" estimating, it may be concerned about its ability to successfully negotiate a price for the implementation phase on an "open book" basis vis-à-vis a more sophisticated or experienced contractor. This can be mitigated by requiring an agreed upon estimating methodology and cost model to be developed upfront and by requiring the contractor to develop a program as part of the preconstruction work for the project owner's approval, to train the project owner's staff on the cost model and related procedures, historical data, categorization of costs, estimating techniques and tools, hardware, software, and any other systems employed by the contractor for cost estimation for the project.

- Use of an independent cost estimator to carry out an independent pricing analysis and validation of the contractor's cost estimate (for example, to avoid "gold-plating" by the contractor), with a mechanism for reconciliation of the independent cost estimator's analysis with the contractor's cost estimate.

- Benchmarking of prices to similar projects, which requires a sufficient pool of similar projects.

- Competitive solicitation of subcontractors by the contractor during the preconstruction phase to perform various parts of the scope of the implementation work (see Diagram 2). This should drive value on the parts of the scope that are being priced by multiple prospective subcontractors. It also means the entire subcontractor market should be available because they are not divided among various bidder teams, as they would be during the RFP stage. Therefore, the project owner can get the most highly qualified team across the full project scope and for all disciplines. For example, for the Potrero Yard Modernization Project, the San Francisco MTA required the lead developer for the project to competitively bid its debt financing, design-build contractor and maintenance provider for project implementation.

- Include a key terms sheet for the implementation agreement (i.e., DB contract or P3 agreement) in the RFP so that these terms are agreed upon prior to selection and not subject to negotiation later.

5. Align project owner culture and contract management and administration

- The project owner needs to have the willingness and flexibility to employ a new approach to contracting that may be a significant departure and disrupt its typical "business as usual" processes. The project owner should consider whether to implement change management processes for this purpose. Without effective planning and education around a progressive contracting model, the project owner's culture and contract management and administration processes may be difficult to change.

- In order to give effect to the collaborative nature of progressive contracting, the project owner will need to focus on establishing clear expectations and goal alignment with the contractor and an approach that is less adversarial than may be customary in the administration of a fixed-price contract. This needs to be reflected in the governance structure to monitor and manage the contracting process. This should look like a partnering approach between the project owner and the contractor and may include blended project teams and the colocation of staff.

- The project owner's standard contract management and administration policies or protocols may also need to be modified for progressive contracting.

CONCLUSION

- Progressive contracting models can be a useful tool for project owners to employ under the right conditions and, when properly understood, can improve the likelihood of project success.

- There will inevitably be some trade-offs that public owners need to consider when deciding whether to use a fixed- price delivery model or a progressive contracting model. For example, there may be a concern from project owners that competitive tension for project implementation is reduced, but engaging a contractor at the preconstruction stage may also reduce the private sector's perception of risk associated with the project and increase its willingness to bid. Progressive contracting likely requires an additional commitment of time and resources by the public owner early in the project development process, but it has the potential to produce a better defined and more financially feasible project.

- The five guiding principles set out in this article can help project owners achieve the successful implementation of well-crafted progressive contracting by: (1) ensuring reasonable certainty of a deliverable project; (2) maximizing opportunities for optimization of project risk management during the preconstruction phase to drive value; (3) carefully considering preconstruction scope costs to correctly incentive the contractor; (4) applying mechanisms to mitigate a perceived lack of competitive tension in pricing project implementation; and (5) aligning project owner culture and contract management and administration.

- Ashurst has advised public owners on numerous progressive contracting projects across the US and internationally, including Maryland DOT, LA Metro, the City of San José, and San Bernardino County.

The authors would like to thank Adam Sheets (Garver), Sia Kusha (Plenary Americas) and Will Gorham (Plenary Americas) for providing their views and input in connection with this article.

1. For convenience, we use the term "contractor" throughout this article to refer to the counterparty to the project owner under a progressive contract, but depending on the type of progressive contracting model this counterparty could be better described as a "developer" or some other entity.