It's all about the get-up – Recent product packaging decisions

25 July 2023

It is becoming increasingly difficult for brands to protect their product packaging or "get-up" from being copied or adapted by competitors seeking to leverage the customer trust, goodwill and recognition earned by other brands. This issue is becoming increasingly prominent due to the fact that the get-up of a product may contain elements or themes that are common to a particular product, trade or industry, which makes it difficult to establish that the company which created the original packaging has a monopoly over it or that the alleged infringer intentionally copied the get-up of the applicant's product. In February alone, there were two Federal Court decisions illustrating the difficulties faced by applicants in these types of disputes.

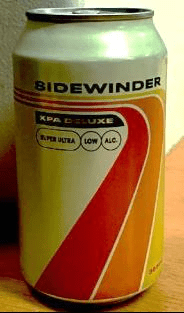

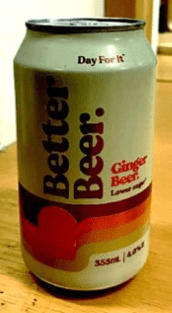

In this case, the applicant produced beer and other related products, including a no and low alcohol beer branded as "Sidewinder". The applicant alleged that the respondents engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of the ACL by using similar get-up to the applicant to promote and sell its beer and ginger beer products under the brand "Better Beer". The products in dispute are depicted below with the applicant's "Sidewinder" product on the left and the respondents' "Better Beer" product on the right.

The applicant's product was launched 5 days before the respondents' and were said to have been each developed independently of the other. The applicant submitted evidence of two instances of consumer confusion in support of its claim.

Justice Stewart dismissed the application, finding that he was not satisfied that a consumer of beer would have had any particular familiarity with the "Sidewinder" product and its get-up (given how new it was), but even if they did, they would not have been misled by the get-up of "Better Beer" product because of the distinctive names used for each of the products as well as the differences in the get-up (eg, placement of the different elements). While Justice Stewart accepted that there were instances of actual confusion, they were at most instances of momentary confusion and the consumers were not mislead or deceived in any material way.

In this case, the applicant commenced proceedings against the respondent arguing that the respondent engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct by representing that the coconut water it sold under the brand "Nature's Delight" was made or sold with the permission of the applicant. The applicant asserted that those representations were made by the type of packaging used by the respondent.

The applicant's packaging is depicted below on the left. The respondent's packaging, which it has used since early 2022 is depicted on the right.

Following a mediation the parties entered into a settlement agreement in September 2022 after which the respondent designed new packaging it intended to use (depicted on the right above). The agreement was purportedly terminated by the applicant on the basis that the new packaging did not comply with the terms of the agreement.

Justice Nicholas dismissed the application stating that he was not persuaded that the respondent adopted any of its new packaging for the purpose of appropriating the reputation of the applicant. While Justice Nicholas accepted that the person who created the respondent's new packaging likely saw the "Raw C" product on sale and that influenced her design, he did not accept that it was intentionally copied for the purpose of misleading any consumer or in order to take advantage of the applicant's reputation.

Justice Nicholas also noted that some of the similar elements are common to the trade including the size and shape of the packaging and that the colours used (shades of blue, white and green) are often used on the packaging of coconut water. He concluded that there was no reason for a consumer to infer that the product sold under the "Nature's Delight" brand was made by or with the permission of the applicant.

On the settlement agreement, Justice Nicholas found that it was validly terminated by the applicant because the applicant acted reasonably in concluding that the terms of the agreement were not complied with (ie, regarding the development of the new packaging).

In both Federal Court decisions the presiding judges considered a number of relevant factors to determine if a product's get-up was misleading or deceptive.

In the Better Beer Case, his Honour considered the following factors:

In the Natural Raw C Case, Justice Nicholas considered the following factors:

In each case, the key cause of action was a claim that the respondent had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, rather than the tort of 'passing off'.

Passing off is when a business misrepresents its goods, services or brands as the goods, services or brands of another party; this is a common law tort in Australia. To establish the tort of passing off, it must be established that there is a reputation in the relevant goods/services/brands and that the business suffered or is likely to suffer damage as a result of the passing off.

In the Raw Natural C Case, passing off was pleaded and it was agreed between the parties that if the applicant succeeded under s 18, then it would also succeed in a claim for passing off. Given the result, Justice Nicholas did not address the passing off claim. No passing off claim was made in the Better Beer Case.

In contrast to the tort of passing off, although reputation is relevant, it is not a strict requirement to establish a contravention of the ACL.

If an applicant fails to establish that its product and get-up has some reputation or distinct association with the product in the minds of consumers, it will be difficult to prove the likelihood of a consumer being misled or deceived by a respondent adopting a similar get-up. To this point, reputations built side by side make it difficult for applicants to allege misleading or deceptive conduct.

In the Better Beer Case, Justice Stewart found that the exposure of the Sidewinder get-up to consumers of beer and their familiarity with its get-up was minimal. His Honour stated that although it is not necessary to establish a particular reputation in an existing product, it is still necessary to establish some association in the mind of consumers. Any such association cannot be assumed and any claimed public familiarity with features of the get-up must be established. Without a pre-existing association, the use of a similar get-up alone will not be sufficient to establish a claim for misleading or deceptive conduct.

In the Better Beer Case, Justice Stewart affirmed that the relevant date for the assessment of misleading or deceptive conduct is the date promotion commenced rather than the date of the product's first sale because this establishes the beginning of reputation.

Consumers are unlikely to be misled in instances where one product causes momentary confusion with another product that is capable of being overcome on closer examination through the use of distinctive product names or the different arrangement of packaging elements.

In the Natural Raw C Case, the Court found that Raw C's Director, Mr Mendelson's mistake of thinking Nature's Delight was his company's product could be overcome by a double take and the absence of the Raw C device mark at the front of the packaging. Similarly, in Better Beer, Justice Stewart found that confusion merely arose from a fleeting observation that led to, at most, momentary confusion.

In the Natural Raw C Case, Justice Nicholas recognised that in some industries there is likely to be similarities in packaging due to the nature of a product. In the Natural Raw C Case it was observed that the size and shape of the packaging, colour of the cap, and the use of colours such as blue, white and green were frequently used by companies in the coconut water market. Justice Nicholas referred to the comments made by Justice Bennett in Natural Waters of Viti Ltd v Dayals (Fiji) Artesian Waters Ltd (2007) 71 IPR 571 at [46] to support his reasoning; Justice Bennett stated: "by their nature, goods of different manufacturers will bear some resemblance to each other".

Whilst copycat products create a lot of frustration for manufacturers, in the wake of these two decisions, it will be interesting to see if these types of claims relating to product get-up will continue to remain difficult to establish.

Of all the relevant considerations, establishing a strong reputation in a product's get-up appears to be the key to meeting the high threshold to prove confusion amongst consumers. This high threshold may deter future allegations from being brought but these cases provide useful commentary on the importance of reputation and the extent to which brands are able to use similar product packaging elements to those of their competitors.

Authors: Lisa Ritson, Partner; Lachlan Wright, Senior Associate; and Kimberly La, Graduate.

The information provided is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all developments in the law and practice, or to cover all aspects of those referred to.

Readers should take legal advice before applying it to specific issues or transactions.